Huntington’s Disease: This is the least you must know

Published on 7th April, 2022

Authors: Pragya Rathore, Shrevya Shankar

Abstract: Huntington’s disease is a progressive neurodegenerative, autosomal-dominant disorder that damages the brain cells and causes cognitive and behavioral impairment with the hyperkinetic movement disorder (chorea). It highly impacts movement, thinking, mood, personality, and speech as well. Accumulation of the toxic proteins in the brain leads to neurological symptoms. Since Huntington’s disease affects the brain physiology, it is a serious condition. Due to its heritability, however as of now, it cannot be prevented or cured, so patients should focus on managing the symptoms associated with it.

Huntington’s disease (HD), also known as Huntington’s chorea, is an inherited disorder that affects the brain. It primarily alters the personality, memory capabilities, and mood changes in an individual. George Huntington discovered it in 1872. The disease itself is found in 2% of people in their childhood and 5% of the people, who were older than 60. Huntington’s causes problems with a person’s ability to think, behave and move. Gradually, the disease leads to a loss of function, hindering the ability to carry out daily tasks and loss of independence.

Huntington’s disease typically manifests between the ages of 35 to 45 years, but the early onset can range from 2 to 80 years old. If the condition develops before the age of 20, it is called Juvenile Huntington’s Disease. The symptoms can appear at any age but when develops early, the disease might progress faster. The progression of Huntington’s disease in terms of symptoms in younger people might differ from that in adults. Juvenile HD progress at a faster rate with greater cognitive decline.

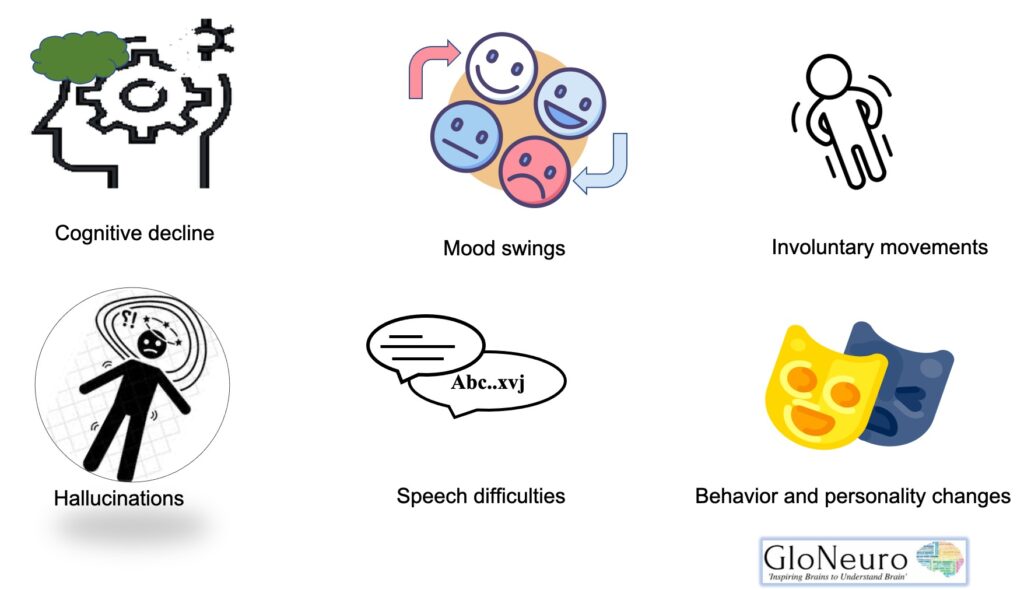

Symptoms

- Early clinical signs

Depression, Anxiety, Agitation, Delusions, Hallucinations, Irritability, Clumsiness, Apathy, Abnormal eye movements, Olfactory dysfunction, Mood swings, Memory lapses

- Middle clinical signs

Dystonia, Involuntary movements, Weight loss, Speech difficulties, Trouble walking, and balancing, Stubbornness, Slow reaction time, Inability to control speed and force of movement, Chorea, Memory loss, OCD, Bipolar Disorder

- Late clinical signs

Rigidity, Bradykinesia (difficulty initiating & continuing movements), Significant weight loss, Inability to walk, Inability to speak, Swallowing problems, Severe chorea

Genetics of HD

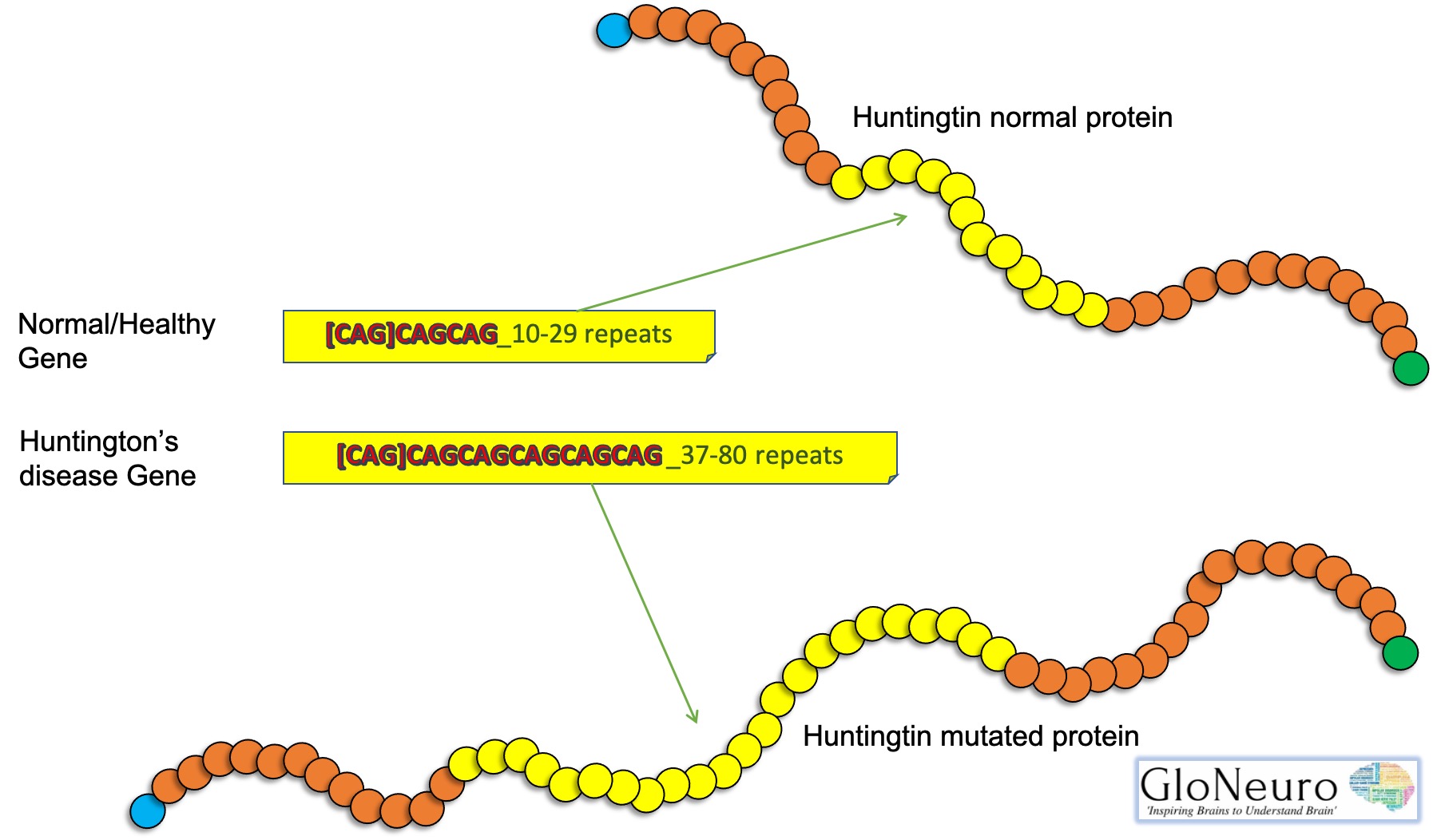

The Huntingtin gene (HTT) codes for Huntingtin Protein (Htt) and everyone has two copies of the HTT gene which lies on the short arm of chromosome 4 and contains a CAG (cytosine-adenine-guanine) repeat known as trinucleotide repeat. CAG is a genetic code for the amino acid Glutamine. So, the CAG repeats result in the production of a chain of glutamine known as the polyglutamine tract.

A mutation may increase the repeat count and results in a defective gene. When the length of this repeated section reaches its threshold due to a mutation produces an altered protein, called mutant huntingtin protein (mHtt), which causes pathological changes and increases the decay rate of certain neurons. The Htt protein interacts with over 100 other proteins. Research studies show that mHtt is toxic to brain cells and the early damage is evident in the subcortical basal ganglia, initially in the striatum but as the disease progresses, affects certain brain regions including the cerebral cortex.

| Repeat count | Classification | Disease status | Risk to offspring |

| <27 | Normal | Will not be affected | None |

| 27–35 | Intermediate | Will not be affected | Elevated, but <50% |

| 36–39 | Incomplete Penetrance | Risk of developing in lifetime | 50% |

| 40+ | Full penetrance | Will be affected | 50% |

Alleles with 36-39 CAG repeats exhibit incomplete penetrance. Disease risk varies on the absence of CAA the has been termed as the loss of interruption (LOI) variant.

- 36-39 repeats. Approximately one-third of symptomatic individuals have [(CAG)n-CAA-CAG] interrupted repeat

- 36 and 37 repeats. The majority of symptomatic individuals have a pure [(CAG)n] repeat.

Development of the disease

The gene that causes Huntington’s disease is dominant, which means that only one mutated gene from either parent is required to produce the disease. The defect occurs when the CAG normal base sequence, is repeated several times. The Huntingtin gene carries instructions to make the huntingtin protein. A messenger RNA is created from the DNA to carry the signal to the cellular factory for protein synthesis. Unfortunately, too many CAG repeats produces toxic form of the protein, known as mutant huntingtin protein. In addition to impairing neuronal transport networks and gene regulation, mutant huntingtin proteins damage them in many other ways as well.

Huntington’s is increasingly recognized as a disease of the whole brain and body. Areas of the brain responsible for cognition, personality, and movement are particularly affected, leading to the classic triad of symptoms of Huntington’s disease. The initial symptoms of Huntington’s disease are variable in different individuals. However, it is common for the disease to advance faster in all patients if initial symptoms have appeared early. Mood swings and irritation occur for no discernible reason at first.

These early symptoms are not noticed by the individual, but they are evident to family members. Affected individuals experience depressed moods and a lack of motivation to do almost anything. Some individuals may notice a reduction in their symptoms as the disease progresses while others may experience continuation accompanied by violent episodes. Due to the memory loss associated with Huntington’s disease, the patient may experience trouble learning new things and performing basic tasks such as driving.

It is also challenging to recall routine information and make decisions. Others may lose their capacity to comprehend when their handwriting changes. Others have uncontrollable movement of their fingers and feet, which becomes more pronounced when the person is anxious.

Complications of the disease

In severe cases of Huntington’s disease, the patient falls more often while walking due to a loss of balance. In due course of time, individuals become incapable of eating, talking, or even recognizing their family members. Health risks are indeed associated with an inability to eat due to a lack of a balanced diet and essential nutrients.

Neuropathology

In case of advanced Huntington’s disease there can be about 25% loss of brain weight. Neuronal loss in striatal part of basal ganglia underlies the most evident symptoms in affected individuals.

Degeneration of the enkephalin-containing neurons of the indirect pathway of movement control in the basal ganglia provides the neurobiological basis of chorea and the loss of substance P- containing neurons of the direct pathway results in akinesia and dystonia.

Treatment

Huntington’s disease is currently not curable. The treatment plan includes medications to only manage the symptoms the medicines have a few side effects that might worsen the other symptoms.

FDA has approved two medications to treat Huntington’s disease which include Tetrabenazine (Xenazine) and Deutetrabenazine (Austedo) to suppress involuntary movements (chorea).

Further medications involve Antipsychotic drugs, Antidepressants, and Mood stabilizing drugs for psychiatric disorders.

Psychotherapy, Speech therapy, Physical therapy, and Occupational therapy can significantly improve the quality of life.

Reviewer: Areeba Aziz, Dr. Jitendra Kumar Sinha

Illustrations: Shrevya Shankar, Dr. Jitendra Kumar Sinha

Editor: Dr. Shampa Ghosh

References

1. Caron NS, Wright GEB, Hayden MR. (1998) [Updated 2020 Jun 11]. Huntington Disease. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2022.

2. Walker FO (2007) “Huntington’s disease”. Lancet. 369 (9557): 218–28. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1. PMID: 17240289

3. Nance MA. (2017) Genetics of Huntington disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 144:3-14. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-801893-4.00001-8. PMID: 28947123.

4. Ghosh R, Tabrizi SJ. (2018) Clinical Features of Huntington’s Disease. Advances in Experimental Medical Biology. 1049:1-28. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71779-1_1. PMID: 29427096.